(Kwiverr Missiology Series #2)

INTRODUCTION

Having already established Missiology as an actual, formal interdisciplinary subject that studies the theology, history, cultural engagement and strategy of (Christian) mission, we shall now attempt to, in this second installation of the Kwiverr Missiology Series, prove Missiology as an authentic academic discipline with deep historical roots.

CHICKEN AND EGG SCENARIO

Missiology is the study of God’s mission (missio Dei), true, but also of the church’s witness (missiones ecclesiae), and the world’s transformation. While for generations Theology has been considered a legitimate academic discipline, Missiology has not even been heard of by most people I’ve encountered, let alone to be settled in people’s minds as an authentic subject in the academy.

Meanwhile, some have boldly claimed “mission is the mother of theology” (Martin Kähler (1835–1912) and others) because theology in its truest sense did not emanate from a bunch of nerdy people in some ivory tower contemplating the existence and workings of God. No, it was in attempting to reach different people and places with the same unchanging gospel that one realized they ought to put into precise words their beliefs and experiences, and in such a way that the recipient can hear it for themselves in their context. In that missional attempt, therefore, theology is born. If mission per se is “the mother of theology” how about Missiology then?

EARLY HINT OF THE ACADEMIC LEGITIMACY OF MISSIOLOGY

When I first met the revered Missiology professor Andrew F. Walls in person I was delighted to learn from him that he and Prof. J.H. Kwabena Nketia, my ethnomusicologist professor grand dad, had been good friends. Of course Walls had been frequenting the Akrofi-Christaller Institute of Theology Mission and Culture in Akropong, Ghana which grandpa, a lifelong Presbyterian, was the first Chancellor of. Prof. Kwame Bediako and Rev. S.K. Aboa, the founding fathers of this astute African missiological hub both happen to be my chaplain at the Ridge Church School and paternal granduncle respectively. It stands to reason that a Christian academic would recognize and study Missiology, and at a Christian establishment like Akrofi-Christaller, but how about in the wider academy?

The reason I mention Andrew Walls in particular is that I was amazed at how much of his work in Missiology was a bona fide part of, and highly celebrated in, the general ’secular’ academy. Walls was a foundational figure in the study of ‘World Christianity’, a form missiology often takes today, and was instrumental in creating academic centers dedicated to this study, such as the Centre for the Study of Christianity in the Non-Western World at the University of Edinburgh (1987). Liverpool Hope University has a research centre named in honour of him, which encourages and supports research in the field of African and Asian Christianity. Friends I have come to know from the Lausanne Movement circles, like Lausanne’s current catalyst for diasporas, Dr. Sam George, studied under him.

FOUR FORMS OF ACADEMIC LEGITIMACY

Typically, the academic legitimacy of Missiology has been displayed in four ways (4Ps):

- PLACES—Taught, examined and researched in leading seminaries and major universities worldwide. For example seminaries like Fuller and Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and universities like Yale, University of Edinburgh, Pontifical universities, Boston University, University of South Africa (UNISA) etc. have chairs, centres, and/or doctoral programs in Missiology (although it might be under the guise of other names as will be shortly discussed under ‘Placements’).

- PLACEMENTS—Nestled in academic homes in larger bodies like Theology, World Christianity and Intercultural Studies. Some seminaries treat Missiology as applied Theology while it requires deep engagement with fields like biblical exegesis, cultural anthropology, linguistics, global history, and leadership studies.

- PUBLICATIONS—Discussed and debated in peer-reviewed journals and societies of Missiology. For example Missiology, International Bulletin of Mission Research (IBMR), and Mission Studies publish rigorous scholarship. Some societies of Missiology include American Society of Missiology and the International Association for Mission Studies.

- PARALLELS—Considered parallel to applied disciplines like Medicine, Education and Business. The fact that these are applied fields does not take away their rigour or deny their academic legitimacy.

A BIT OF MISSION/MISSIOLOGY HISTORY

The Jesuits (the Society of Jesus), in the 16th Century, are credited with popularizing the term “mission” in its modern, Christian sense—but not with inventing the concept of mission itself (of course), which is as old as the Church. The word missio existed earlier in Latin theology, but the Jesuits gave it its distinctive missional meaning and institutional use. The Latin root Mitto, which means to send, is where we get missio(n), and other English words like transmit and dismiss.

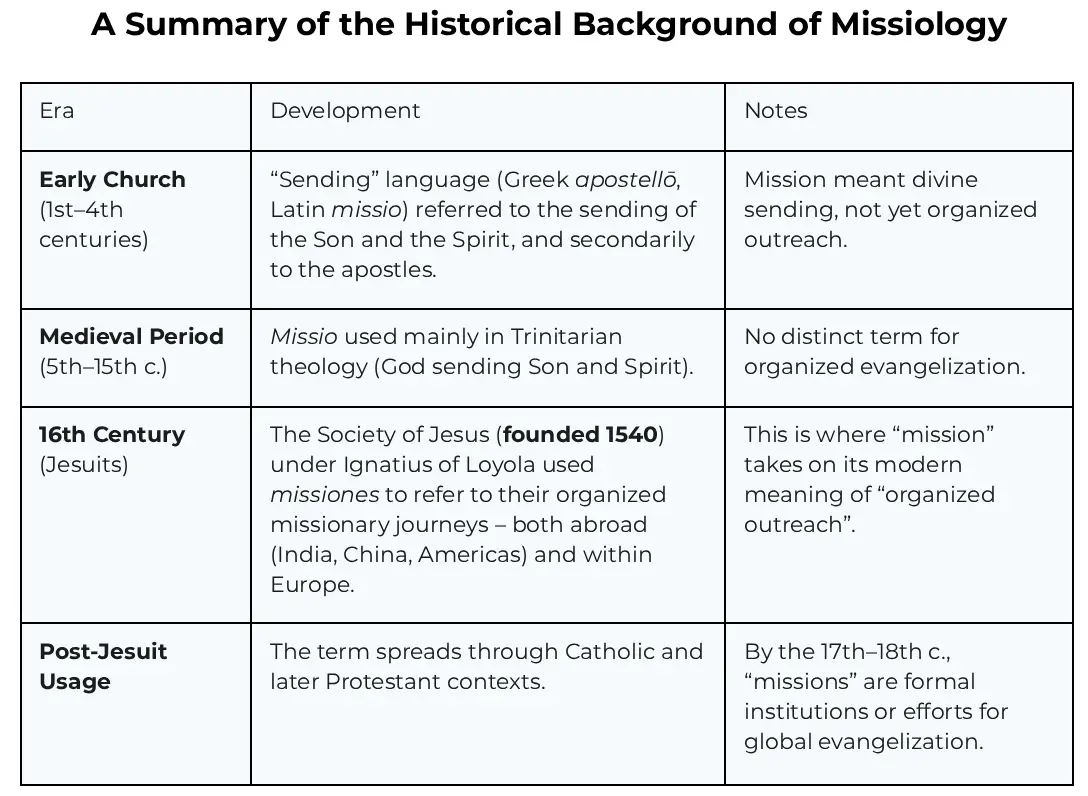

But “sending” language (Greek apostellō, Latin missio) in the early first to fourth century Church period primarily referred to the sending of the Son and the Spirit, and secondarily to the apostles; mission meant divine sending, not yet organized human outreach. Of course, many African church fathers like Athanasius of Egypt and Tertulian from Tunisia participated in and contributed to the shaping of theology and missiology in the early Church, from Africa. In fact, Andrew Walls calls Origen the African a ‘systematic theologian.’ [1]

Even in the Medieval Period (5th-15th c.) missio was used mainly in Trinitarian theology (missio Dei), a period which, again, African theologians like Augustine from Algeria deeply shaped. So the Jesuits (founded in 1540) under Ignatius of Loyola were pivotal in using missiones to refer to their organized missionary journeys, both abroad (India, China, Americas) and within Europe. This is where “mission” takes on its modern meaning of “organized outreach.” Post Jesuit, the term spread through Catholic and later Protestant contexts such that by the 17th to 18th centuries, “missions” had become the norm for formal outreach institutions and/or global evangelization efforts.

Missiology took the form of missionary manuals in the 19th century while in the early twentieth century academic chairs began to spring up in the study of mission(s) as well as the ecumenical roots of the subject. The mid twentieth century was very consequential to mission and Missiology as David Bosch (another African) and Leslie Newbigin re-introduced ‘Missio Dei theology’ that changed everything and distinguished mission (vertical, divine purpose) from missions (horizontal, human practices), again. In the late twentieth century the Global South began to be recognised, again, as well as the interdisciplinarity of the subject emphasized. The twenty-first century has World Christianity and Intercultural Studies as the most fanciful garbs for Missiology with specific streams like ‘Diaspora Missiology’ introduced by the likes of Prof. Enoch Wan, and with other strands like ‘digital mission/missiology’ to boot.

Belgium-born Pierre Charles (1883-1954) was the first to use the term “Missiology”—instead of say ‘missionogy,’ like the Germans were using missionswissenschaft even before the first world war—and to introduce the word in the academy. He used it first in his “Missiology Weeks of Louvain” in the early 1920s. In 1929, the year after the French Academy rejected this concept, he published an article entitled “La missiologie.” The reason for this rejection of the term might be what Pierre Charles framed as an “etymological heresy.” The word is the association of two roots: the Greek “logie” and the Latin “missio.” [2] Still, the title of ‘father of Missiology’ is given to the German Gustave Warneck (1834-1910) as a pioneer of missiology who held a number of firsts: first professorial chair of its kind in the science of missions as an academic discipline (Halle, Germany, (1897-1908); the first to initiate an objective and responsible treatment of missiological topics in his monthly journal Allgemeine Missions-Zeitschrift (1874); the first to produce a comprehensive compendium on the science of missions (1892-1903); and the first to promote effective cooperation in missions by means of conferences on local, regional, and national levels that were later to lead to the creation of a representative central agency of German Protestant missions. [3]

What we have just done above in placing historicity and history at the front to prove Missiology as an authentic academic subject is actually the very essence of Missiology itself. For the subject places history front and near-centre as understanding mission requires knowing how missions developed through the ages—both in early Church and modern mission expansions. If you hate history, you wouldn’t love missiology.

CONCLUSION

From missio Dei (the sending of God) to missiones ecclesiae (the missions/sendings of the Church) to later missiology (the systematic reflection on mission) that re-introduced missio Dei in the middle of the last century, Missiology is a bona fide subject of rigorous academic study with profound historical antecedents. As theologically and historically rooted as it is socioculturally and practically engaged, Missiology is neither fringe nor outdated. It’s evolving as the church itself evolves. It has a complex, contested past but an even more vibrant future as it is being shaped more and more by the Global South (I promise a future instalment in the series on that) and by broader interdisciplinary engagement than by old Western mission models. The areas of the Global South where Christianity is booming had better make room for Missiology in the mainstream; not just at the periphery of Bible Schools and seminaries or the fringes of the fringes of mainline universities. For leaders, missiology is not optional. It equips the church to think deeply, be faithful and act wisely as we engage globally in God’s mission. Today.

REFERENCES

[1] Gitau, Wanjiru. 2022. ‘The Lifework of Andrew Walls for African Theology: Re-centering Africa’s Place in Christian History.’ Lausanne Movement. See https://lausanne.org/global-analysis/the-lifework-of-andrew-walls-for-african-theology-2

[2] Enyegue, Jean Luc. “Charles, Pierre, SJ (1883-1954): Pioneer of Catholic Missiology.” Boston University. https://www.bu.edu/missiology/missionary-biography/c-d/charles-pierre-1883-1954/

[3] Boston University. Warneck, Gustav (1834-1910): Pioneer of missiology as an academic discipline.” https://www.bu.edu/missiology/missionary-biography/w-x-y-z/warneck-gustav-1834-1910/ |(This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Mamillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.)